Music has been central to the Moravian Church from the earliest times. Moravian life was not divided into sacred and secular spaces — all of life was “to be a liturgy, an act of worship” because all activities served the Savior and the congregation. Since the very beginning of the Ancient Unity, music had a position of importance in their lives as a part of their daily and constant worship.

The Brethren began writing hymns of their own as soon as they formed the Unity. They quickly became known for their prolific hymn writing and composing — which has continued for over 560 years and around the globe.

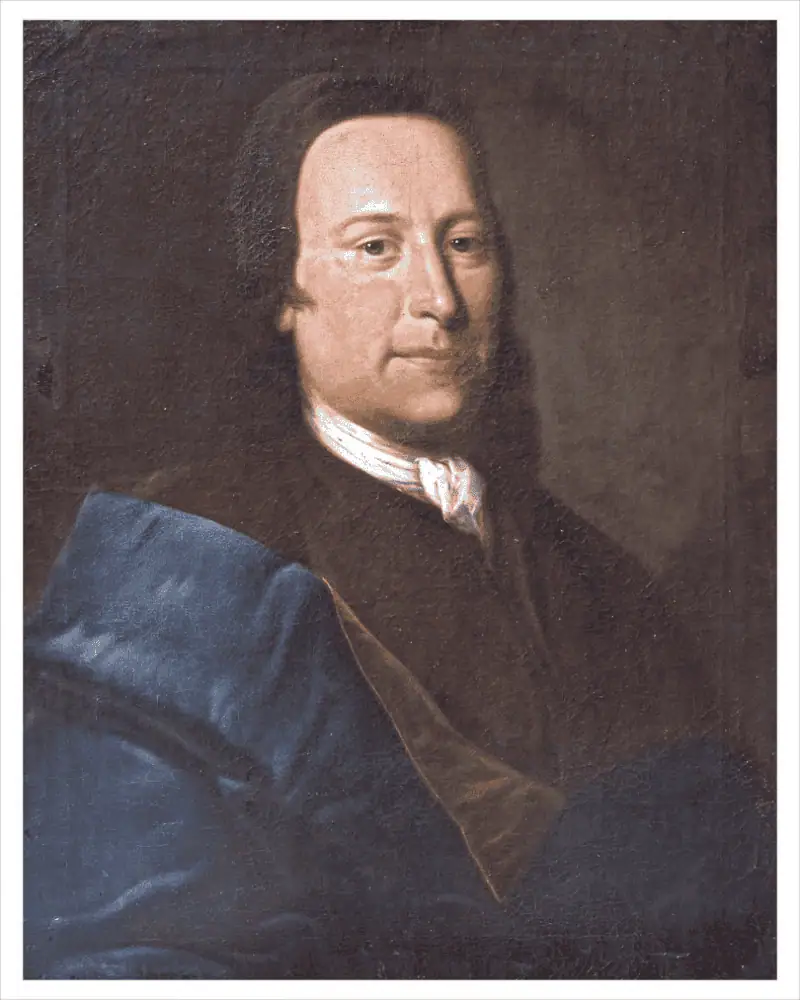

Christian Gregor, known as the Father of Moravian Music, said “the truest language for heart religion is song.” Moravians wrote hymns to give an outlet for and preserve spiritual experiences of the writers. Hymns are how the Moravians express, confirm, and teach their beliefs.

Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf regarded music as the “fifth gospel” and as the best means of communicating directly to the heart. He used music as a tool for theological teaching. Moravian hymns translated abstract thoughts into down–to–earth terms for the congregations to better understand. As he stated: “The heart may know what the mind cannot understand.”

The Ancient Unity

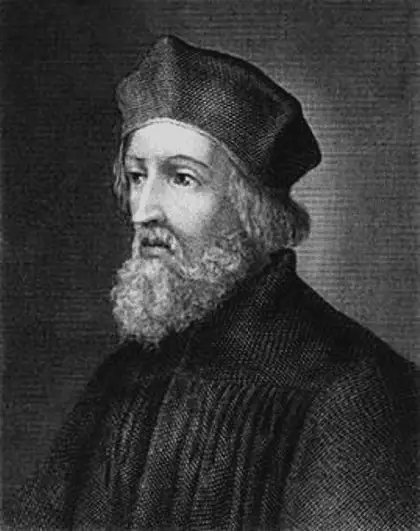

Jan (John) Hus understood the value of the worship–song of the church. In his writings he frequently explained his views regarding singing in the church. He declared song to be one of the forms of devotion that constitute the services of “the heavenly temple in our home (heaven).”

Hus translated into Bohemian some of the Latin hymns the people had been hearing in worship. Other hymns were composed or adapted from Latin by writers now unknown. He also composed hymns himself. Our current hymnal, Moravian Book of Worship, contains one hymn by Jan Hus. Used for Holy Communion, it has ten verses written by Hus in about 1410. (MBW #419)

The Unity of the Brethren relished the idea of singing praises in their own language. This was not allowed by the Catholic Church of Hus’ time, and was a point of contention. Worshiping in their own language symbolized their equality in the eyes of God and their unity as brothers and sisters in Christ.

One of the earliest known hymns of the Unitas Fratrum is Radujme se vždy společně. It has been attributed to either Matěj (Matthias) of Kunwald in 1457 or Gabriel Komarovsky in 1467. It is known as the “ordination hymn of the Ancient Unity.” This hymn alludes to the struggles of the Hussites from 1415 to 1457. Today, we know this hymn as Come, Let Us All with Gladness Raise. (MBW #519)

Unity Hymnals

A Czech hymnal was produced in 1501. It had eleven hymns written by Lukáš of Prague, the most influential theologian of the Unity. This hymnal contained 89 hymns overall and is known as the “First Protestant Hymnal.” Some early scholars claimed it was Moravian because of Lukáš of Prague’s involvement. However more recent research does not connect it directly to the Unitas Fratrum.

The Unitas Fratrum published its first official hymnbook in the Bohemian language at Jungbunzlau, in Bohemia, in the year 1505. It contained versions of Latin hymns as well as original compositions, mostly by Jan Hus and Lukáš of Prague. This hymnal contained 400 hymns and was most likely edited by Lukáš and his brother Jan Černý. Unfortunately, no surviving copy is known to exist today. A hymnal from 1519 was edited by Lukáš, but copies are again lost to history.

Over the next 160 years, the Unitas Fratrum printed eleven different hymnals in Czech, German, and Polish. In addition, Joseph Theodor Müller documents twenty–eight publications that are revisions or expansions of one of those eleven. Clearly, the Unity took its hymn singing seriously!

The first German–language Unity hymnal was published in 1531. Ein New Gesengbuchlen contained 157 hymns. Editor Michael Weisse had translated four hymns from the old Latin Canzional–buch and sixteen from the Czech hymnal of 1519. Several of the hymns were compositions by Weisse, and the rest were most likely selected from hymns composed by German members of the Unity. It is the most comprehensive of the early hymnals in the German language and was reprinted at least four times over the next ten years.

Bishop Jan Blahoslav was the main editor of two of the most important editions of the Unity of the Brethren hymnbooks, one printed in 1561 in Szamotuły, Poland and then reprinted in 1564 in Ivančice, Moravia. The 1561 hymnal contains 744 hymn texts and over 450 melodies, including sixty from the 1501 book. It was reprinted or reissued at least nine times over a 50–year period. A copy is preserved in the Unity Archives in Herrnhut.

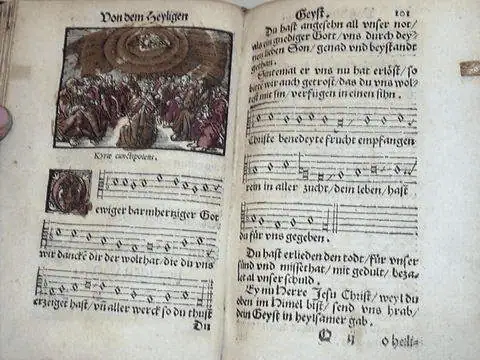

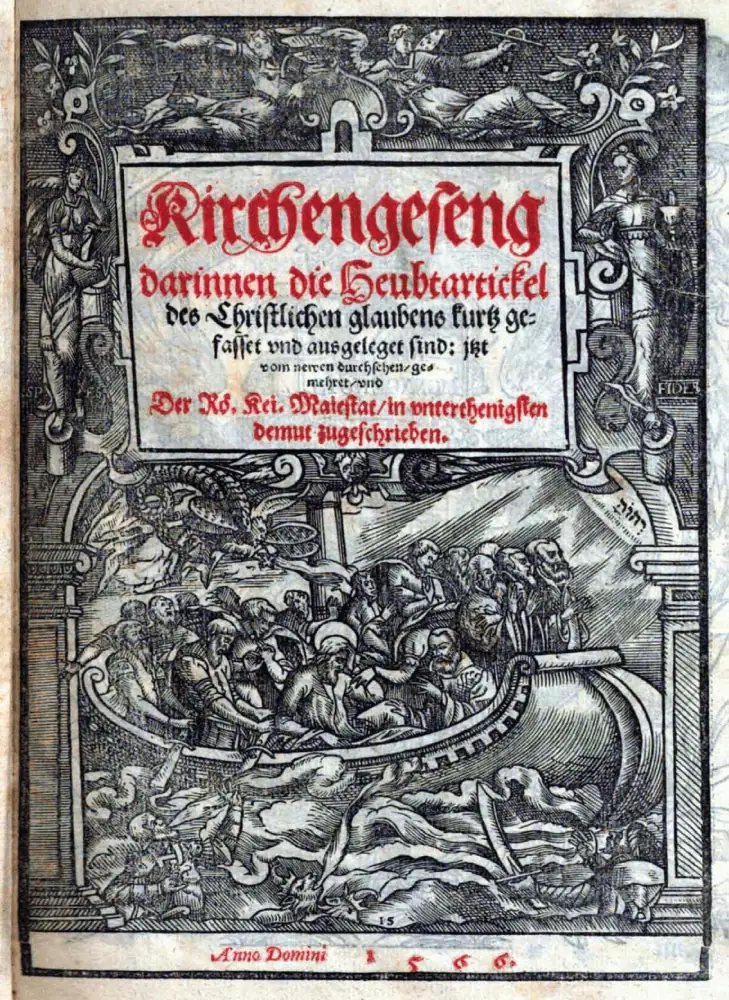

An enlarged German hymnal, Kirchengeseng, edited by Petrus Herbert, Michael Tham the Elder, and Jan Jelecký was published in 1566. It contains 348 hymns with an appendix containing an additional 108 hymns composed by Lutheran authors. This hymn book was reprinted, unaltered, at Nürnberg, in 1580. Later editions of the hymnal appeared in 1606, 1639, and in 1661 which was edited by John Amos Comenius.

In the preface of the 1569 Polish edition of the Brethren’s hymnal, Bishop Andrew Stefan wrote, “Our fathers have taught us not only to preach the doctrines of religion from the pulpit, but also to frame them in hymns. In this way our songs become homilies.”

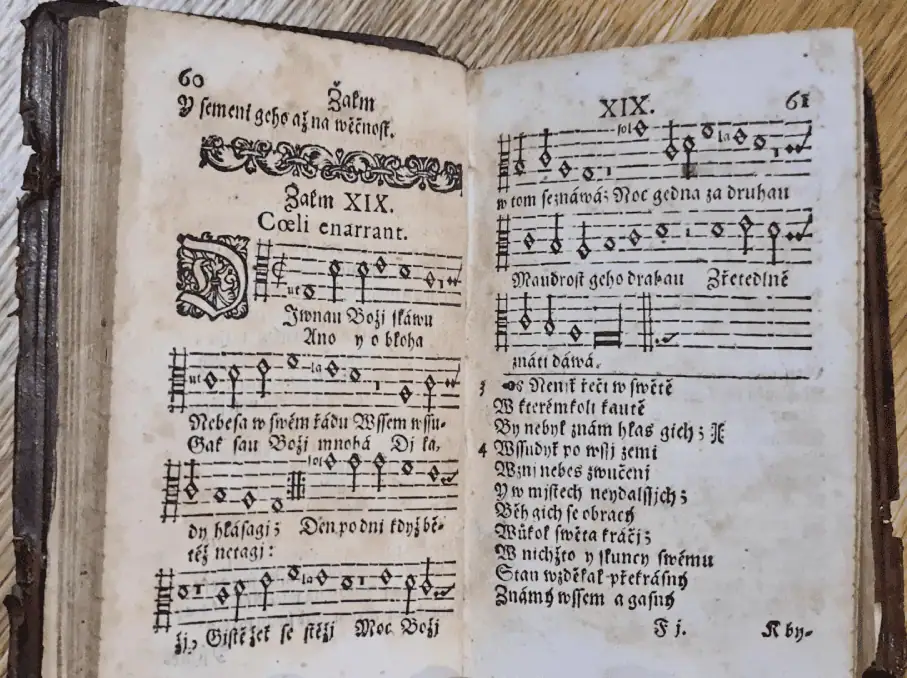

Jiří Strejc’s Czech psalm paraphrases, Žalmové neb Zpěvové svatého Davida (Psalms or Saint David’s Songs), composed under the French melodies of the Genevan Psalter (1539), were printed for the first time in 1587 in Kralice. It contains some minor poems in Latin, six songs in German, and two major versified compositions in Czech. Next editions were made by Prague printers in 1590, 1593 and 1596. The last edition in his lifetime was printed in 1598 in Kralice.

Strejc is probably best known for his German–language hymn text, Mit Freuden Zart. The tune for Mit Freuden Zart is very familiar to today’s Moravians as it is used in the Moravian Book of Worship four times, perhaps the most well–known of which is Sing Praise to God who reigns above, the God of all creation. (MBW #537).

Unfortunately, most of these songbooks were destroyed in the Thirty Years War which began in 1618. Two years later, the Protestants were defeated in the Battle of White Mountain near Prague. The Unity of the Brethren was outlawed and they were forced to go underground. The 1648 Peace of Westphalia guaranteed the right to practice any of the recognized denominations: Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. There were no provisions made for the Unity and it remained outlawed.

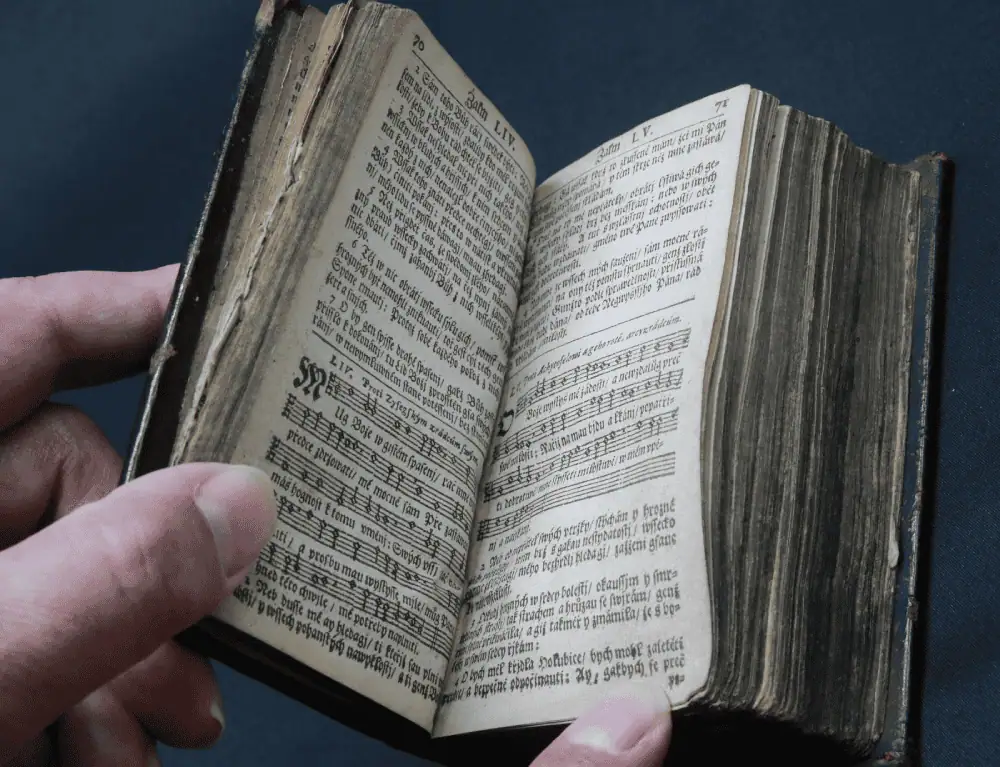

The last of the Czech–language hymnals of the Unity of the Brethren was published in 1659. The Kancionál was edited by John Amos Comenius (Jan Amos Komenský ) who was living in exile in Amsterdam. The preface has important insights into music and worship at the time.

Comenius believed that hymnals should be inexpensive and small enough to be carried in one hand (with the Bible in your other hand). It contains 606 psalms, songs, and choral chants, which were used in public Brethren worship as well as in private spiritual exercises or meetings.

John Amos Comenius died in Amsterdam in 1670, praying that someday the “hidden seed” of his beloved Unitas Fratrum might once again spring to new life.

The Renewed Moravian Church

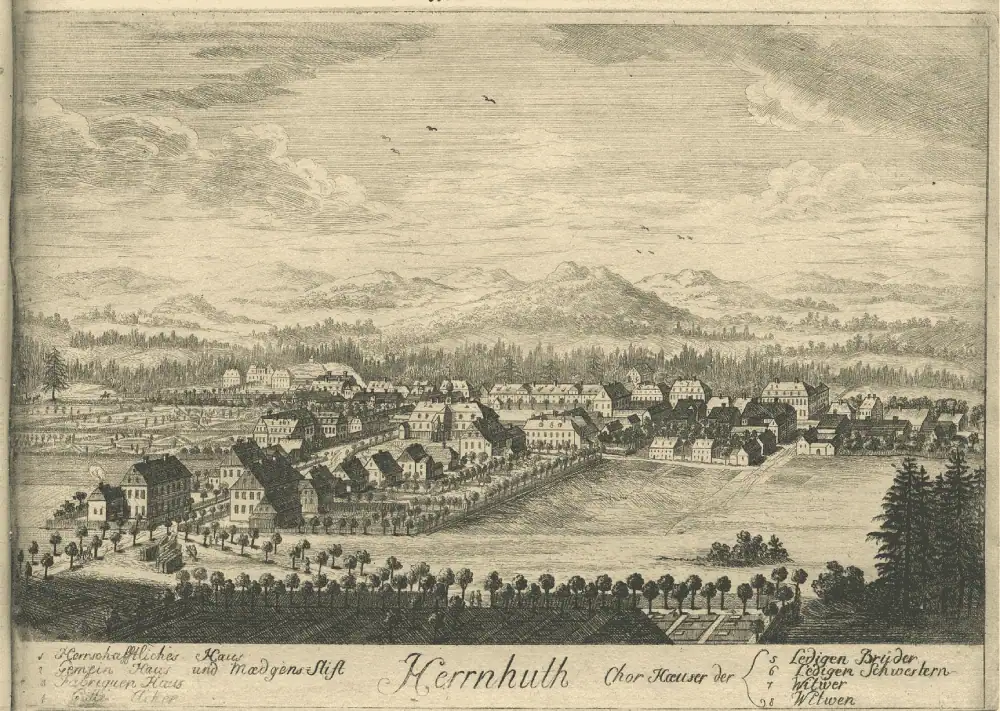

While the Unity of Brethren was driven underground, dispersed, and nearly destroyed, Comenius and others took care to see that its writings survived. In 1722, when some of the German–speaking descendants of the Brethren found refuge on the estate of Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, they brought with them their love of music, their instruments, and their hymns.

From their 200–year heritage of producing hymnals in the Unity, they were accustomed to hymns with theological depth and significance. They were used to producing hymnals. And they were moving into a region already rich with a hymn–singing tradition — hymns written by Martin Luther and Paul Gerhardt.

Count Zinzendorf was a great lover of music, and it became an ever-present part of life at Herrnhut. He strongly encouraged the development of hymn singing and heavy emphasis was placed on memorization. In the early days of Herrnhut, he conducted singing classes in which not only the hymns, but something of the life and purpose of the author was learned.

Altogether, Zinzendorf is credited with the authorship of more than 2,000 hymns! The first was written when he was twelve, and he was still producing hymns in 1760, the year he died.

His most famous hymn is Jesus, Still Lead On, which has been translated into ninety languages. Although it is not as famous as Jesus, Still Lead On, his hymn The Savior’s Blood and Righteousness is perhaps the one hymn most representative of his theology. The count wrote the thirty–three stanzas of this hymn in 1739 on his voyage home after visiting Moravian mission work in the West Indies.

The origin of the Singstunde is attributed to Count Zinzendorf. The Singstunde is a service composed entirely of congregational hymn singing. Over time, the Singstunde became his favorite form of public worship. Zinzendorf went so far as to suggest that one could better judge the health of a congregation by the power of its singing than by its preaching.

Music In Herrnhut

As was the case with the early Unitas Fratrum, the Moravians’ passionate devotion to Christ poured forth in thousands of new hymns in dozens of printed text–only hymnals. Three years after Herrnhut was founded and two years before the August 13th spiritual renewal, Count Zinzendorf published a hymnal of 889 hymns (containing twenty–eight of his own) in 1725. In the next decade he published four other hymnals. One contained 1,416 hymns!

Throughout the history of the Moravian church, instruments have been used consistently in worship as well as in entertainment. In 1731 the Herrnhut collegium musicum was started, based on the earlier European concept of an amateur association for the practice and performance of chamber and orchestra music.

Part of the purpose of such an organization for the Moravians was to give the musicians the opportunity to hone their skills for participation in the many worship services held as central to the life of the community.

This commitment to making music required a significant commitment to music education. All students in Moravian schools received a thorough grounding in vocal music. Children in schools sang hymn tunes and chorales as part of their instructional program. They were also encouraged to learn to play instruments, including keyboard, winds, and strings. Both girls and boys received this musical education.

The first Moravian hymnbook was published for the congregation at Herrnhut in 1735. This hymnal, Gesangbuch der evangelischen Brüder–Gemeinen in Herrnhut — also known as the Herrnhuter Gesangbuch — contained 999 hymns (only two were from the earlier Unity, with 208 by Zinzendorf). Twelve appendices and supplements brought the total number of hymns to 2,357 by 1748.

This hymnal also marks the beginning of a 200–year practice of printing the “hymnal” (Gesangbuch) separately from the “tune book” (Choralbuch), a practice that continued in Germany through the end of the twentieth century.

Influential Hymnals & Tune Books

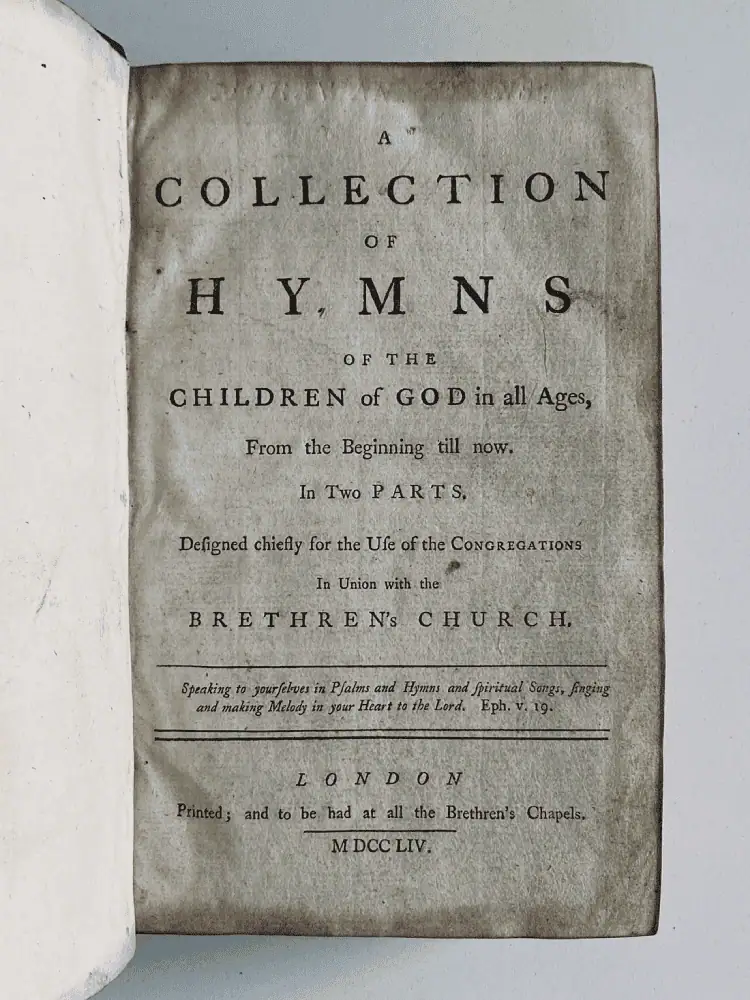

The first official hymnal of the Moravians in England was a very large hymnal, published in London in 1754. Its official title is “A Collection of Hymns of the Children of God in All Ages, From the Beginning till now. Designed chiefly for the Use of the Congregations in Union with the Brethren’s Church”. Better known as Alt und Neuer Brüder Gesang or Das Londoner Gesangbuch, it contains 3,264 hymn texts from the early Unity, the Lutheran Church, the Reformed Church, and the Moravian Church.

The texts, in German and English in parallel columns, emphasized the fact that the Moravians thought of themselves as standing in continuity with the Early Church and as part of the Universal Church. Issued in two parts, the first is a chronologically arranged collection of German hymns of all ages (2,168 hymns in number) published in 1754. The second part, published in 1755, contains the hymns of the Brethren’s Church in the 18th century (1,096 hymns).

In 1755 a Choralbuch manuscript was compiled by Johann Daniel Grimm, containing almost 1,000 hymn tunes. Grimm pioneered the practice of numbering hymn tunes. Tunes with the same metrical structure (same number of lines, same number of syllables in each line, and similar accentuation pattern) have the same number and are distinguished from each other by a letter — e.g., 22 A, 22 B, and so on.

The incorporation of newly composed pieces (anthems, solos, duets) into the services for festival days is what is most characteristically known as “Moravian music.” Christian Gregor, a very familiar name to modern day Moravians, began composing anthems for worship in 1759. He arranged “Psalms”, or lovefeast odes, which had anthems and solos interspersed with hymns in the order of worship. Over the next hundred years, Moravian composers wrote thousands of sacred vocal works, mostly accompanied by strings and occasional wind instruments, for their worship services.

By Zinzendorf’s death in 1760 the need for a smaller hymnal, and one more useful for worship planning, was seen. At the Synod of 1775, Christian Gregor was assigned the task of organizing and editing this immense body of hymns.

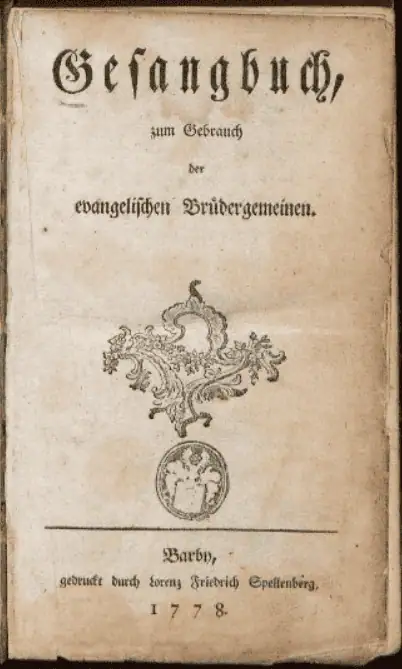

The result was the extremely influential hymnbook Gesangbuch published in 1778. Gregor removed hymns which were not in use, added new ones which had been recently written, and took stanzas of two or three different hymns and combined them into one hymn. The hymnal contains 1,750 hymns, 308 of them written or arranged by Gregor. It also has 261 melody classes and 469 chorale melodies, more than sixty of which are written by Gregor. It was the standard hymnal used in Germany for more than a century.

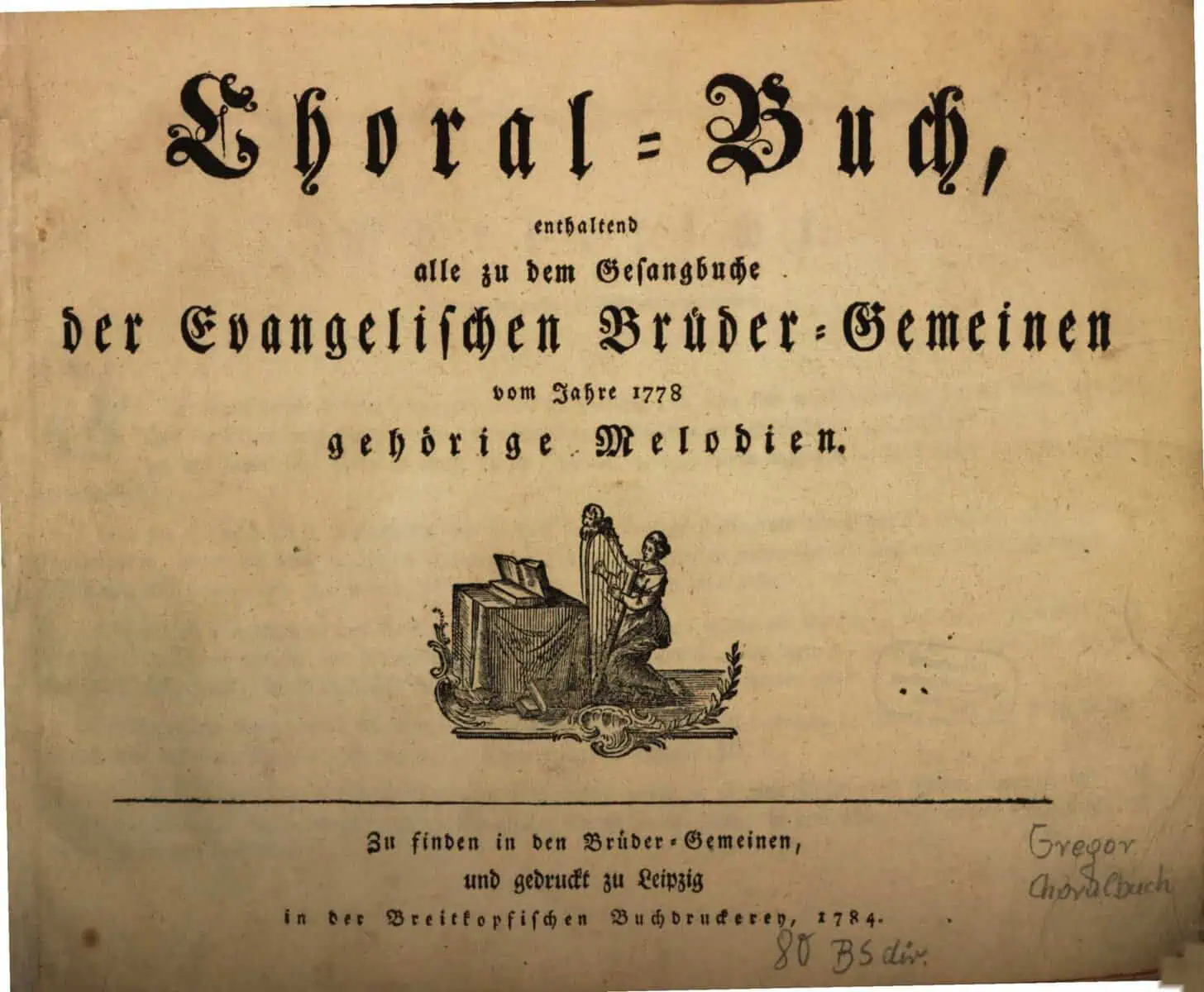

The synod must have been happy with the results, for in 1782 it assigned Gregor the task of preparing a chorale book to accompany the 1778 hymnal. Christian Gregor’s Choralbuch contained the most frequently used tunes for hymns. Gregor cleaned up and added to the tune numbering system developed by Grimm in 1755.

Published in 1784, this book also remained a standard, not only in German–speaking congregations but also around the Moravian unity. Chorale books published in England, America, South Africa, and elsewhere used Gregor’s work as their foundation. Many churches still use this system today, with tunes called by number rather than name, particularly with brass choirs and church bands.

The 1778 Gesangbuch and the 1784 Choralbuch are landmarks in Moravian music history. They have shaped Moravian hymn–singing for more than two hundred years. Copies of these hymnals were sent to Moravian congregations worldwide, and many privately owned copies survive in Moravian archives in Winston–Salem, Bethlehem, and Herrnhut.

Christian Gregor was one of the most flexible and influential Moravians of his time. He served the church as organist, music director, teacher, composer, hymnist, liturgist, pastor, Elder, and Bishop. He introduced arias and anthems into Moravian worship. He helped develop many of the distinct Moravian musical traditions. So great was his influence on the Moravian church and its music that the Moravians claim him as the “Father of Moravian Music.”

In 1789 John Swertner edited the British Moravian hymnbook, A Collection of Hymns for the Use of the Protestant Church of the United Brethren (and its enlarged edition, published in Manchester in 1801). It is recognized as the parent of both the British and American hymnals of today. The hymns are under a liturgical arrangement of forty headings and there is a full index of first lines of all verses. Swertner wrote a hymn to fill up a blank space on the last page of hymn texts, two verses labeled “Eternal Praise” — known today as Sing Hallelujah, Praise the Lord.

The Moravian Church In America

The musical life in the Moravian settlements was rich and became respected by many in the young country. This musical life included sacred vocal music for worship services with hymns and anthems. Brass ensembles, especially trombones, served specific sociological and liturgical functions. Instrumental music for recreation ranged from works for unaccompanied solo instruments to small ensembles to symphonies and large oratorios.

When the Moravians settled in Bethlehem in 1741, Count Zinzendorf carefully chose the inhabitants of this new community according to their skills so they could contribute to the mission work of this new village. Therefore, it was not accidental that many of the leaders, artisans, and workers were also musicians.

Instruments In Worship

Instruments came to America with the Moravians. By 1742 Bethlehem had flutes, violins, violas da braccio, violas da gamba, and horns. These instruments were played not by professionals but by accomplished amateurs, who enjoyed orchestral and chamber music as well as accompanying vocal solos and anthems for worship.

In 1744 the collegium musicum in Bethlehem was founded under the direction of Johann Christopher Pyrlaeus. Director Johann Friedrich Peter in Bethlehem made the collegium musicum a regular part of worship in 1773. The Moravians in Bethlehem were now hearing musical instruments during worship every week. The Nazareth collegium musicum was founded in 1780, which would be a vehicle for numerous musical performances.

In early 1744 a spinet arrived in Bethlehem, PA. The spinet suffered damage during the voyage but was repaired for use in the following day’s worship service. In 1759, John Antes made one of the first violins in America and opened an instrument–making shop in Bethlehem in 1762.

Wherever the Moravians went an organ soon followed. The first pipe organ of Bethlehem was installed in 1746. David Tannenberg arrived in Bethlehem in 1749. He is cited as the most important American organ–builder of his time. He constructed nearly 50 organs (in six states) during his lifetime, as well as other keyboard instruments. Tannenberg organs were built with such excellence that his surviving organs are highly prized today.

The Moravian Historical Society in Nazareth, PA is home to this 1776 pipe organ made by David Tannenberg and the 1759 violin made by John Antes. Photo courtesy of the Moravian Historical Society.

In 1762, just a few years after arriving in what is now North Carolina, the Moravians played an organ for the first time. It had arrived via ship and wagon from Pennsylvania to a tiny settlement called Bethabara.

In 1754, a complete choir of trombones (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) was sent to the new colony, and the Bethlehem Moravian Trombone Choir was born.

In 18th–century Moravian settlements the trombone choir, playing from the church tower or from in front of the entrance, served to call the congregation to worship, and served as the congregation’s “portable” ensemble for accompanying outdoor services such as burials and the Easter sunrise service.

The trombone choir would also announce deaths in the community and generally served as the settlement’s “public address” system.

During the nineteenth century many trombone choirs incorporated other brass instruments. The development of valves allowed musicians to play a wider range of notes, including scales and chromatic passages, making them much more versatile and essential to orchestras and bands. Adding valved instruments such as trumpets, French horns, euphoniums, and tubas changed the sound of Moravian brass choirs.

Most Moravian congregations today have a trombone choir, a brass choir, or a church band, which incorporates woodwind instruments as well. Today’s Moravian congregations have also adopted additional instruments for worship in various parts of the country and the world. The variety of instruments include handbells, guitars, string instruments like violins, violas, and the cello, steel drums, timpani, and harp.

American Moravian Hymnals

As the Moravians established their mission work around the world, they made every effort to produce hymnals in the languages of the people among whom they lived and worked.

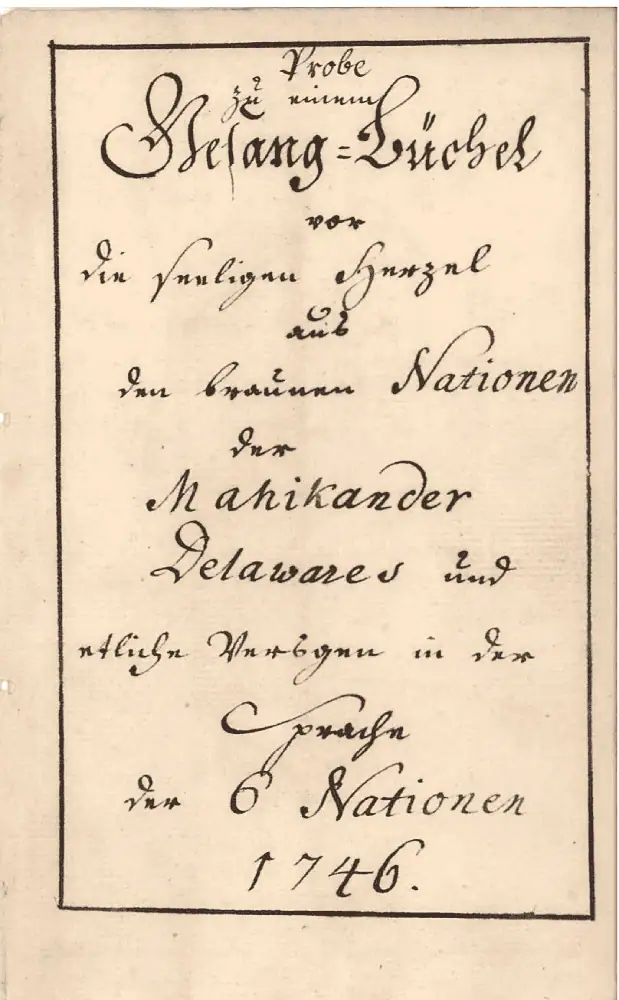

In 1746, members of the Native American Mohican tribe from the community of Shekomeko, New York composed new native–language hymns with Moravian missionaries who lived among them. In 1803 A Collection of Hymns for the Use of the Christian Indians, of the Missions of the United Brethren in America, prepared by missionary David Zeisberger with hymns in the Delaware language, was published in Philadelphia. The second edition debuted in 1847.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Moravians in America used German and English hymnals from Europe. A Moravian hymnal was printed in Philadelphia in 1813, but the first independently edited American English–language hymnal was published in America in 1851. It followed in detail the English hymnal of 1849, but with some significant variations.

It contained 1,000 hymns compared to the English selection of 1,261 and some were added by the American revision which meant they dropped 300 or more of the English selections. The American hymnal was printed again in 1853, and subsequent printings were made in 1866, 1872, 1875, and 1876, when a new revised edition was issued.

A new and revised American hymnal was issued in 1876. The editor of the brief preface wrote, “It has been the great aim of all those connected with this work to bring the new Hymn book up to the standard of modern hymnology, without destroying its Moravian character”. They again added some hymns and discarded others and rounded off the number at 930.

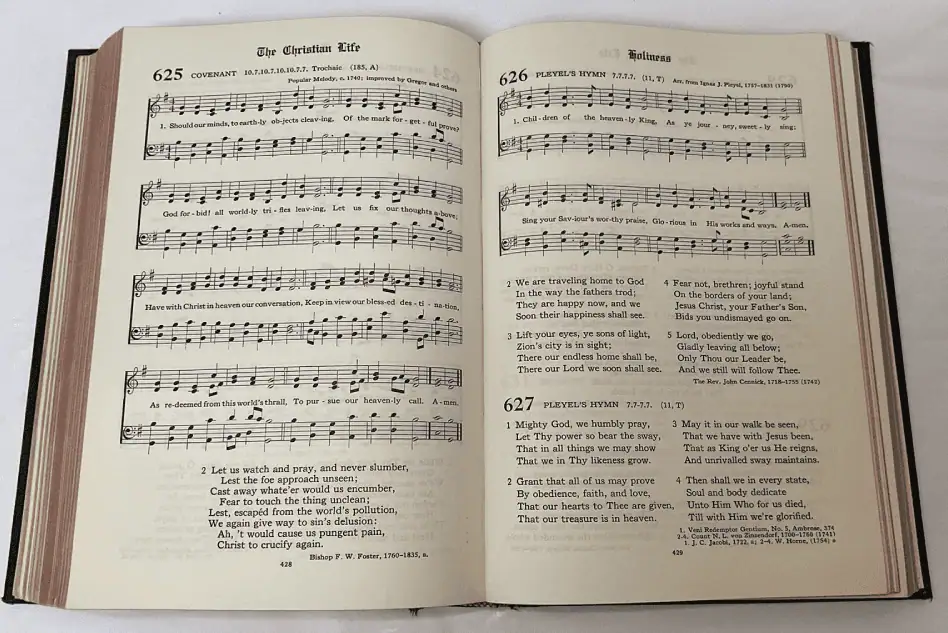

The 1876 American hymnal remained in use until the 1920 Hymnal and Liturgies of the Moravian Church (Unitas Fratrum) was produced. The 1920 hymnal (colloquially known as the black hymnal) took the inclusion of printed music a step farther. Hymns were arranged topically, and each hymn was assigned to a specific tune, with the first verse interlined in the music.

This hymnal too had a long (and still quite revered) “pew life.” Some congregations retained it long after the production of a revised Hymnal and Liturgies of the Moravian Church in 1969.

In the 1969 book, up to four verses were placed between the musical staves. It included a few new hymns but had three hundred fewer hymns in total than the 1923 hymnal. The “red hymnal” as it has been known was very popular, and some hymns not included in the 1995 hymnal are still used in many Moravian congregations.

The American provinces produced a truly “new” hymnal in 1995, the Moravian Book of Worship. The MBW includes a larger percentage of hymns by contemporary authors and composers. Several hymns exemplify a newly emerging trend in Moravian hymnody of using a refreshing musical style with a text that maintains the primacy of an intimate personal relationship with Christ. This is the hymnal currently in use in the American province churches.

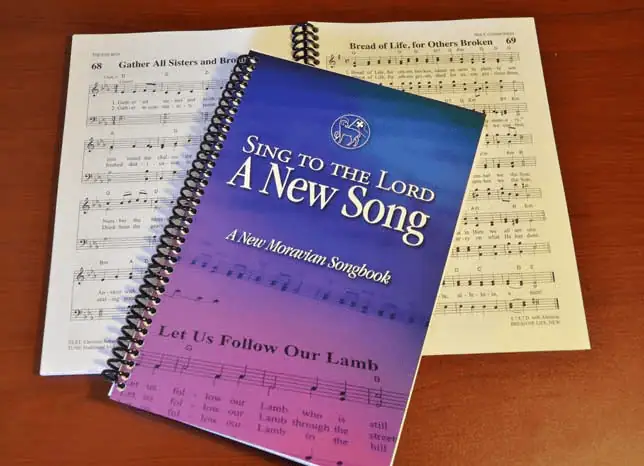

Sing to the Lord a New Song: A New Moravian Songbook was published by the Moravian Music Foundation in 2013. The songbook celebrates the musical gifts of today’s Moravian Church in North America and features 80 all-new songs and hymns by 51 writers and composers. It offers a glimpse at the creativity and spirituality that is alive and well in Moravian music today.

New texts by Moravian hymn writers recognize the changing nature of the worship experience in the North American congregations. New texts continually appear in the Caribbean area and the African provinces as well, enriching the tapestry of Moravian worship. As Franz Florentin Hagen’s tunes did a century ago, tunes by American Moravian composers of the late twentieth century continue to reflect the influence of classical training, the sound of traditional Moravian hymns, and a concern for contemporary–sounding music.

Moravian Composers

The Moravians believed that musical ability, like every other gift, was to be used in praise of Christ and for the good of the community, not for the benefit of the individual. Of the music written by Moravian composers, by far the greater portion is what today is called “sacred” — anthems and solos for liturgical use. However, they did copy and collect thousands of works, vocal and instrumental, by their contemporaries in Europe, for use in worship and in the life of the community. Visitors to the Moravian communities were consistently high in their praise of Moravian musical activities.

The composers of Moravian music throughout history have been primarily people with other vocations. Moravian composers of the 18th and 19th century were also pastors, teachers, and administrators, with responsibilities far beyond composing and directing music. These Moravian composers wrote very few pieces of independent instrumental music, though the Moravians used instrumental music extensively for instruction and enjoyment.

Many Moravian composers in the eighteenth century were trained in music by the same composers who influenced Mozart and Haydn. Thus, they came to the New World fully conversant with the taste and practice of European classicism. Few realize it, but much of Europe’s great Baroque and Classical music was first performed in America — not in New York or Philadelphia — but in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania or Salem, North Carolina as Moravians celebrated God’s great gift of music.

Among the most influential, prolific, and/or enduring Moravian composers were: John Antes, Johann Christian Bechler, Jeremias Dencke, Ernst Immanuel Erbe, Johann Christian Geisler, Francis Florentine Hagen, Johannes Herbst, Christian Ignatius Latrobe, Edward W. Leinbach, David Moritz Michael, Johann Friedrich Peter, Johann Christopher Pyrlaeus, the Van Vleck sisters – Amelia, Lisette, and Louisa, John Frederick Wolle, and Peter Wolle.

This list is neither complete nor exhaustive (it just barely makes it into the 20th century!) but includes many of the more prolific and better–known composers of the last 300 years. An exhaustive list would also include hymn composers, hymn text writers, and composers of spiritual songs.

The backbone of traditional Moravian instrumental music is an enormous collection of four–part chorales. Many of them are shared with other, younger Protestant denominations (especially the Lutherans and Methodists), but a large number of the traditional chorales are uniquely Moravian in origin and usage.

During the eighty years from about 1760 to 1840, American Moravians wrote hundreds of anthems, duets, solo sacred songs, and instrumental pieces, and collected hundreds of others — both printed and hand–copied.

In 1765 Johann Friedrich Peter began copying sacred music by contemporary composers like Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn, and Schubert. A year later Jeremias Dencke wrote an anthem for the Provincial Synod in Bethlehem — the earliest example of Moravian concerted (anthem) church music in America.

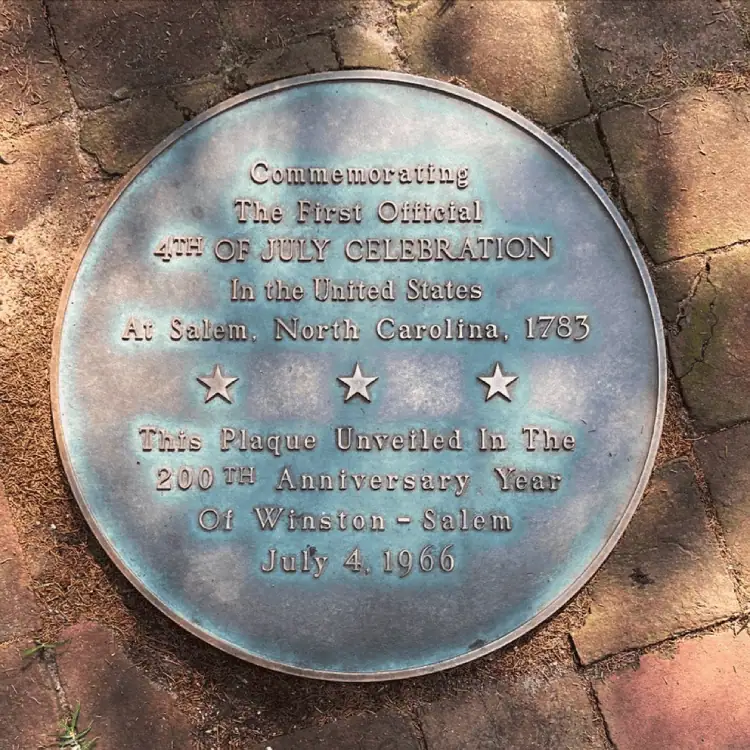

The first documented celebration of Independence Day in the United States of America was held in Salem, NC on July 4, 1783 with the lovefeast Freudenpsalm (Psalm of Joy), planned and organized by Johann Friedrich Peter. The music for the lovefeast was taken in large part from the music used by the Moravians in Germany to celebrate the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. The joyful solo, choral, and orchestral music was therefore a celebration of peace, the end of war, and gratitude to God.

Johann Friedrich Peter’s Six String Quintets written in 1789 are the earliest–known chamber music written in America. David Moritz Michael composed the multi–movement “Psalm 103” presented by the Nazareth collegium musicum in 1805.

Franz Florentin Hagen published Church and Home Organists Companion, two collections of organ music. Published in 1880 and 1882, they include a number of his own compositions based on popular hymn tunes and arrangements and transcriptions of a wide variety of other music of the nineteenth century.

Moravian composers today, like their forebears in the faith, are primarily trained musicians who may or may not be employed in church music, music education, or music performance. Many will have non-music or non-church professions and still serve the Moravian Church through music.

Moravian Music Today

Moravian music is alive and vibrant today! The spread of Moravian mission activity and development of the church far beyond its homelands has resulted in a variety of new hymns by many twentieth and twenty–first century authors and composers.

Moravians are creating new anthems, new hymns, new songs for camp, new arrangements for various instruments in worship, new organ preludes, new handbell pieces, and new descants for hymns.

Hymnals of English–, Danish–, Dutch–, and German–speaking congregations are translated and shared with the world through missions and Unity efforts. Over the years, the Moravian Church has printed hymnals in a great many other languages, including (but not limited to) such languages as Afrikaans, Danish, Dutch, French, Inuit (Greenland), Inuktitut (Labrador), Miskito, Welsh, and Yup’ik (Alaska).

At the same time, North, Central, and South American, West Indian, British, and European congregations are absorbing and utilizing music and hymns from each other, but also from or influenced by a variety of musical cultures in the world–wide Unity, like South Africa, Tanzania, Nicaragua, and Nepal.

As the world gets smaller, Moravians find that “different” and “unusual” makes worship interesting, and that all music brings us closer together in Christian community with each other and with the Savior.

From The Past Into The Future

The Moravian Church has consistently understood the purpose of its hymns and hymn singing. In the preface of every English–language Moravian hymnal since 1789, the following prayer has been included. Similar injunctions appear in the prefaces of hymnals in other languages:

May all who use these hymns experience, at all times, the blessed effects of complying with the Apostle Paul’s injunction (Ephesians 5:18,19), “Be filled with the Spirit, speaking to yourselves in psalms, and hymns, and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord.” Yea, may they anticipate, while here below, though in an humble and imperfect strain, the song of the blessed above, who, being redeemed out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation, and having washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb, are standing before the throne, and singing in perfect harmony with the many angels round about it, “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honor and glory, and blessing, forever and ever. Amen!”

This is the core of the Moravian musical heritage throughout more than 560 years. As a gift of God, music is the language of the heart and the mind in worship. As the people’s expression of faith, music is worthy of great care and effort, including proper education, training, preparation, and leadership. The musical heritage of the Moravians is a living tradition that is still evolving.

Some information on this page has been taken from the Moravian Church In America website. Copyright © 2010–2025, Interprovincial Board of Communications, Moravian Church in America. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from the Moravian Music Foundation website. Copyright © 2025, The Signal Company. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page is from the Moravian Music Foundation’s Lunchtime Lecture “A Time–Line of Moravian Music” by Rev. Nola Reed Knouse, Ph.D. Copyright © 2020 The Moravian Music Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from the essay “Hymnody of the Moravian Church” by Rev. Albert H. Frank and Rev. Dr. Nola Reed Knouse from the book “The Music of the Moravian Church in America” edited by Nola Reed Knouse. University of Rochester Press © 2008 by the Editors and Contributors. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from the essay “Moravians and Their Music” by Rev. Nola Reed Knouse, Ph.D. from the book The Music of the Moravian Church in America edited by Nola Reed Knouse. University of Rochester Press © 2008 by the Editors and Contributors. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from “Early Hymnals of the Bohemian Brethren” (A paper presented at the John Hus Conference, Watertown, Wisconsin, Aug. 5, 1937) by W. N. Schwarze.

Some information on this page has been taken from the article “The Development of the Moravian Hymnal” by The Rev. Henry L. Williams, B.D., M.L.S. from Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1962, pp. 239–66. JSTOR.

Some information on this page has been taken from the article “Methodists and the Moravians” from December 8, 2013, found on the blog Organists Do It With Pedals. All Rights Reserved

Some information on this page has been taken from the article “Wesley, the Moravian Hymnwriter” from October 29, 2015, found on the blog Organists Do It With Pedals. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credit: 1746 Native American Mohican Moravian Hymnal — Image taken from “Strong Wounds: Eight Mohican Moravian Hymns”. Edited by Sarah Eyerly and Rachel Wheeler, Eighteenth-Century Musical Settings by Joshua Tanis, New Musical Arrangements by Brent Michael Davids, Linguistics by Christopher Harvey. © 2022 Moravian Music Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credit: Cover of the “Chorales And Music Of The Moravian Church Band – Green Books” © Moravian Music Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credit: CD cover of “Tumfuate! Songs of the Moravian Women of Tanzania“. © Moravian Music Foundation. All Rights Reserved.