The world–wide Moravian Church, also known as the Unitas Fratrum (Unity of the Brethren), is the oldest Protestant denomination in the world with a rich and unique history dating back to the 15th century. Proud of its heritage and firm in its faith, the Moravian Church ministers to the needs of people wherever they are.

The name Moravian identifies the fact that this historic church had its origin in ancient Bohemia and Moravia in what is the present–day Czech Republic. In the mid–ninth century these countries converted to Christianity chiefly through the influence of two Greek Orthodox missionaries, Cyril and Methodius.

They translated the Bible into the common language and introduced a national church ritual. In the centuries that followed, Bohemia and Moravia gradually fell under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Rome, but some of the Czech people protested.

The Ancient Unity

The Czech Reformation was born of a great revival of faith at the close of the Middle Ages. The foremost of Czech reformers, Jan Hus (1369–1415) was a professor of philosophy and rector of the University in Prague.

Hus emphasized the importance of a personal relationship with God. The Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, where he preached, became a rallying place for the Czech reformation.

Gaining support from students and the common people, Hus led a protest movement against many practices of the Roman Catholic clergy and hierarchy.

Jan Hus was accused of heresy, underwent a long trial at the Council of Constance, and was burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

The Unitas Fratrum

The reformation spirit did not die with Jan Hus however. Within fifty years of his death, a contingent of his followers had become independently organized as the “Bohemian Brethren” (Čeští bratři) or Unity of the Brethren (Jednota bratrská) — officially, the Unitas Fratrum. Hus’ followers gathered in the village of Kunvald, about 100 miles east of Prague in eastern Bohemia, in 1457. A brother known as Gregory the Patriarch was very influential in forming the group, as were the teachings of Peter Chelcicky.

According to Gregory the Patriarch, what made a Christian was not doctrine or what they believed, but that a person lived their life according to the teachings of Jesus Christ.

He described these first Moravians as “people who have decided once and for all to be guided only by the gospel and example of our Lord Jesus Christ and his holy apostles in gentleness, humility, patience, and love for our enemies.” (Rican, History of the Unity)

This was 60 years before Martin Luther began his reformation in Germany and 100 years before the establishment of the Anglican Church in England.

By 1467 the Moravian Church had established its own ministry, and in the years that followed three orders of the ministry were defined: deacon, presbyter and bishop.

Growth & Persecution

The Unitas Fratrum grew rapidly. By 1517 the Unity of Brethren numbered at least 200,000 with over 400 parishes. Using a hymnal and catechism of its own, the church promoted the Scriptures through its two printing presses and provided the people of Bohemia and Moravia with the Bible in their own language. They were able to maintain a living fellowship in Christ with a careful system of discipline and schools for the children.

The Brethren met Martin Luther and other reformers on equal terms, taught them the value of an effective church discipline, and gained from them new insights into the nature of a saving faith.

A bitter persecution, which broke out in 1547, led to the spread of the Brethren’s Church to Poland where it grew rapidly. By 1557 there were three provinces of the church: Bohemia, Moravia and Poland.

The impact of the Unitas Fratrum on the spiritual life in their country, and over the boundaries of their homeland, drew the attention of the Roman church authorities. The Brethren were denounced as heretical and treasonable. In the troubles of the reaction against the Reformation, times of persecution alternated with times of comparative calm.

The Church In Exile

The Thirty Years War (1618–1648) brought further persecution to the Brethren’s Church. The Protestants of Bohemia were severely defeated at the battle of White Mountain in 1620 and the Unitas Fratrum and other Protestant bodies was utterly suppressed by the Roman Church.

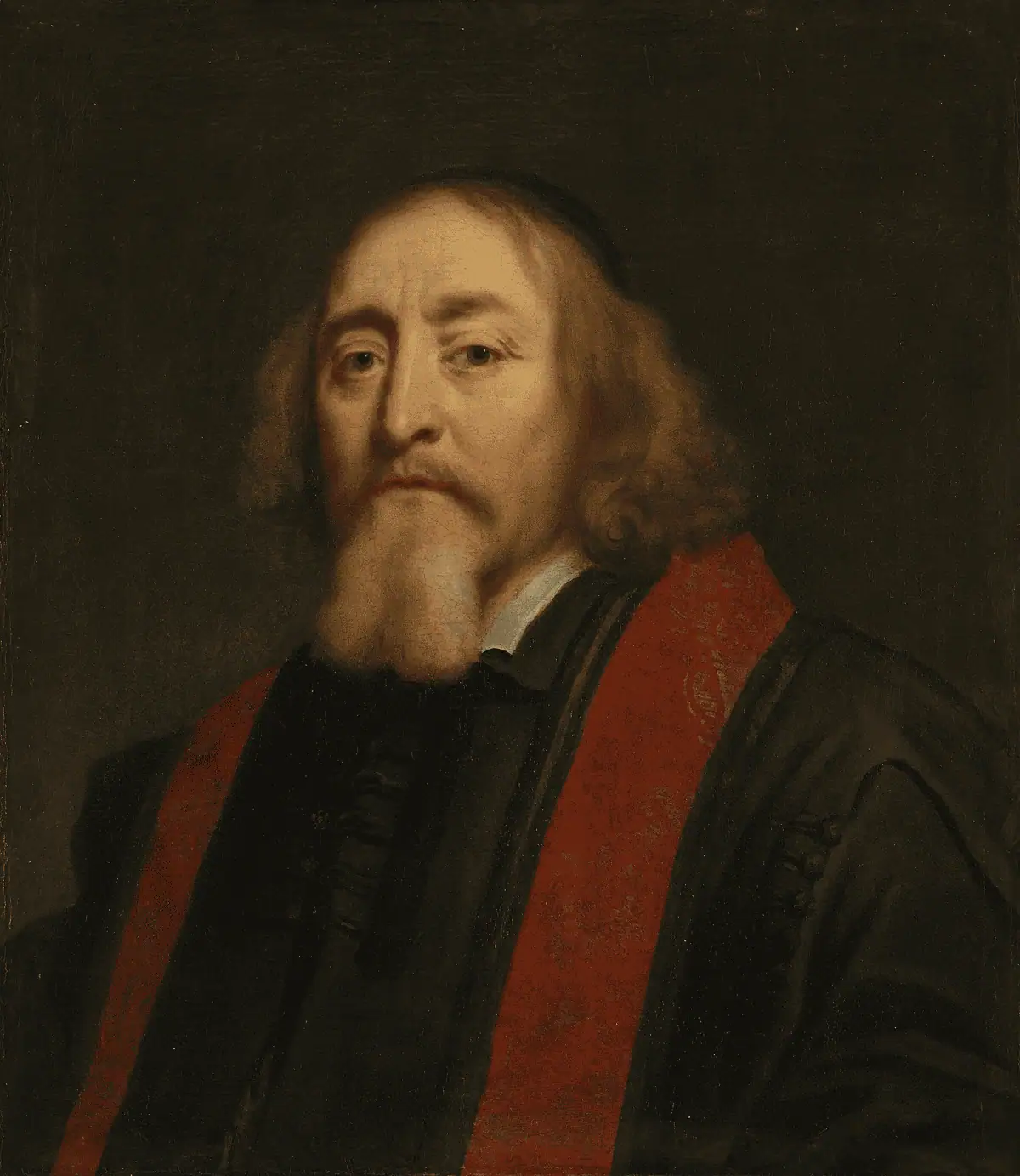

The Brethren were forced to go underground, and eventually dispersed across Northern Europe. Their bishop, John Amos Comenius (1592–1670), attempted to direct a resurgence. The largest remaining communities of the Brethren were located in Leszno (German: Lissa) in Poland and small, isolated groups in Bohemia and Moravia.

The influence of Bishop John Amos Comenius, who had preserved the discipline of the church and was renown for transforming education worldwide, was a great source of strength after the disruption of the church. He never ceased to pray and to plead publicly for the restoration of his beloved church. (Comenius lived most of his life in exile in England and in Holland, where he died in 1670.)

His prayer was that a “hidden seed” of his beloved Unitas Fratrum would preserve the evangelical faith and might someday spring to new life.

The Renewal of the Moravian Church

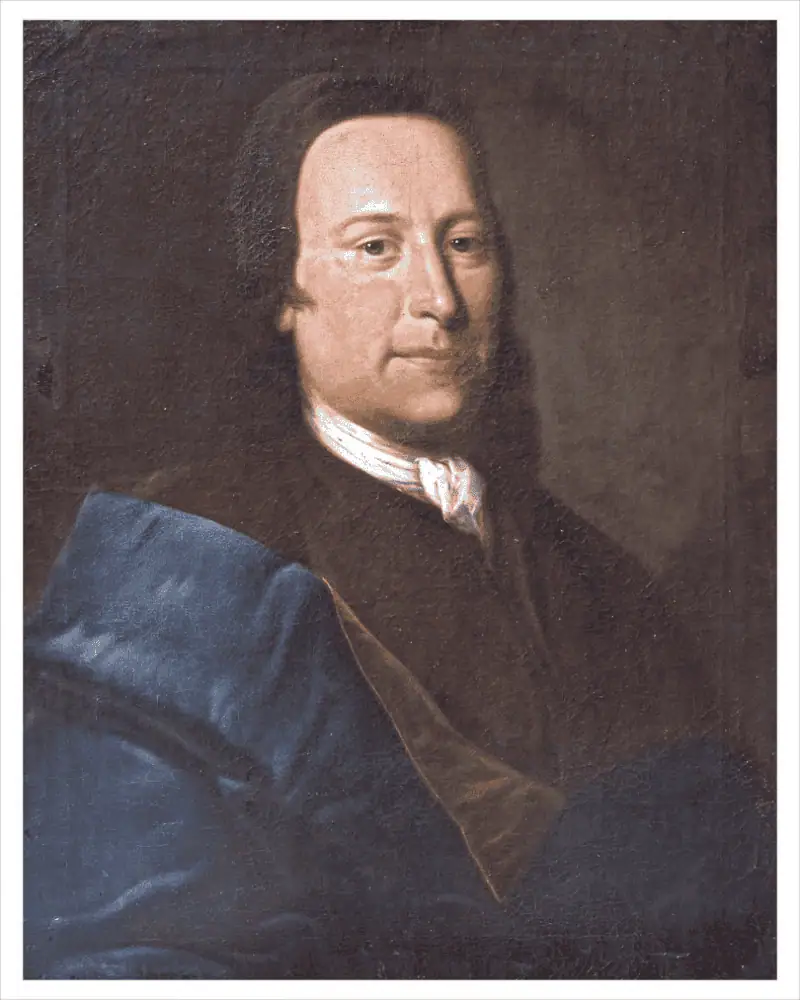

A “hidden seed” indeed survived in Bohemia and Moravia, and emerged a hundred years later in the Renewed Moravian Church through the patronage of Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a pietist nobleman.

In 1722, some families from Moravia, who had secretly kept the traditions of the old Unitas Fratrum, fled from persecution in their homeland. They found a place of refuge on the Berthelsdorf estate of Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760) in Saxony in the eastern part of present-day Germany.

The refugees established a new village, called Herrnhut, which might be translated as “The Lord’s Watch.” The new community became the haven for many more Moravian refugees. Herrnhut also attracted many believers and religious seekers from other places. Zinzendorf became their spiritual leader, as well as their patron and protector against interference from without.

As the community grew, differences among the inhabitants caused serious conflicts, leading to a severe crisis in 1726. Zinzendorf recognized that his intervention was necessary. He quit his regular employment and assumed a stronger leadership role in the Herrnhut community.

The Moravian Pentecost

In May 1727, Zinzendorf introduced a communal covenant, known as “The Brotherly Agreement”, which outlined his vision of Herrnhut as a community based on Christian love. He encouraged the inhabitants of Herrnhut to study the Bible and to pray for one another.

A profound and decisive experience of this unity was given to them in an outpouring of the Holy Spirit at a celebration of the Holy Communion on August 13, 1727. This spiritual awakening transformed the community. They began gathering for prayer, worship, and Bible study with a renewed hunger for God.

From this experience of conscious unity came zeal and strength to share this fellowship in Christ with other branches of the Church universal, and joy to serve wherever they found an open door. Zinzendorf gave them the vision to take the gospel to the far corners of the globe.

Zinzendorf is considered the founder of the renewed Moravian Church and one of the most important theologian and leaders of religious awakening in the 18th century. His effect on the Moravian Church was significant and is still evident nearly three centuries later.

Moravian Missionaries

With this new sense of unity and purpose, the Herrnhut community was transformed to grow into a movement for mission and evangelism of international scope. The renewed Moravian Church was highly evangelical, sending out missionaries around the world.

in 1732 the first missionaries were sent to bring the Gospel to the slaves in the Danish West Indies. Johann Leonhard Dober and David Nitschman boarded a sailing ship in Copenhagen, Denmark, on October 8, 1732, for a nine-week passage on the open seas to the island of St. Thomas.

History records that more than 100 Missionaries were sent from Herrnhut in the first 25 years since the Pentecost experience in August 1727. That’s more than the rest of the Protestant church had sent out in two centuries!

Since then, God’s call to proclaim the good news of God’s saving work in Jesus Christ has taken hundreds of Moravian missionaries from the mountaintops of Ladakh, India to the savannas of La Mosquitia, Honduras.

For more information on the early missionary work of the Moravian Church, please click here.

Moravians In The American Colonies

The Moravians first came to America during the colonial period. In 1735 they were part of General Oglethorpe’s philanthropic venture in Georgia. Their attempt to establish a community in Savannah did not succeed, but they did have a profound impact on the young John Wesley who had gone to Georgia during a personal spiritual crisis.

After the failure of the Georgia mission, the Moravians were able to establish a permanent presence in Pennsylvania in the spring of 1740, settling on the estate of George Whitefield in Nazareth. Whitefield and the Moravians had a falling out, but he would sell the tract to the Moravians when faced with money problems.

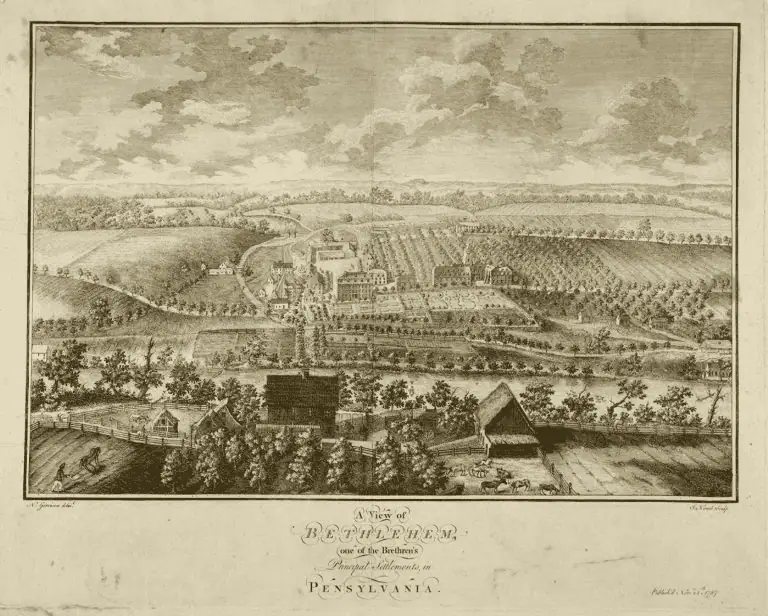

On April 2, 1741, William Allen deeded 500 acres at the junction of the Monocacy Creek and Lehigh River to the Moravian Church. On Christmas Eve in 1741, Count Nicolas Ludwig von Zinzendorf, who was visiting them, led them to a stable, where they sang the hymn “Jesus Call Thou Me.” Its lyrics, “Not Jerusalem — lowly Bethlehem ’twas that gave us Christ to save us.” inspired Zinzendorf to name the settlement Bethlehem. The town grew rapidly from only 131 settlers in 1741 to more than 1,200 Moravians in Bethlehem and the surrounding region by 1753. Bethlehem was the center of Moravian activity in colonial America.

Other settlement congregations were established in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland. They also established congregations in Philadelphia and on Staten Island in New York. All were considered frontier centers for the spread of the gospel, particularly in mission to the Native Americans.

For almost 100 years the American Moravian settlements were primarily closed communities. These communities served both as places where the Moravians could live the life they chose, and places from which many missionaries were sent out. Missionaries were primarily sent to the Native Americans, whose languages the Moravians learned, in order to preach in the language of the people.

The Southern Province

Growth of the Southern Province began not as an isolated mission endeavor like St. Thomas or Greenland, but as “settlement congregations” for church members who were immigrating from earlier Moravian settlements in Pennsylvania or Europe.

Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg led an exploration party of Moravians and surveyors to the backcountry of North Carolina, finally arriving in December 1752 at a suitable site “on the three forks of Muddy Creek” — encompassing almost all of present-day Winston-Salem in Forsyth County.

A total of 98,985 acres were surveyed off, and Spangenberg named the tract “Wachovia,” after an ancestral estate of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf’s. On October 8, 1753, the first colony of Brethren set out from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. They arrived to begin the first settlement in Wachovia on November 17, 1753, and as they held their first lovefeast that evening they could hear wolves howling in the surrounding forests.

The central administrative community of Wachovia was planning for a new community to be located in the heart of the Moravians’ Wachovia — Salem. Work on Salem began in earnest with the felling of the first tree on January 6, 1766. Construction of the settlement continued as Salem grew to be a substantial community. With the consecration of the Gemein Haus on November 13, 1771, the Festival of the Chief Elder in the Moravian Church, Salem was organized as a congregation. More than a century later it would come to be called Home Moravian Church.

From the arrival of the first settlers in 1753 until the organizing of the Hope and Friedland congregations in 1780, the Moravian Church in North Carolina had grown from 12 to 573 members, despite two wars that hindered even greater growth.

The Moravian Church In America

In 1857 the two American provinces, North and South, became largely independent and set about expansion. Bethlehem in Pennsylvania and Winston-Salem in North Carolina became the headquarters of the two provinces (North and South).

The Southern Province grew mainly in Forsyth County, but over time established congregations in Charlotte, Greensboro, Wilmington, Raleigh, and Stone Mountain, Georgia. Moravian churches in Florida are growing with the influx of immigrants from the Caribbean basin.

The Northern Province expanded with the influx of immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia into the upper Midwest in the late 19th century. It now reaches both coasts and as far north as Edmonton, Canada. Green Bay, Wisconsin was founded by Moravians. Such wide geographical spread caused the Northern Province to be divided into Eastern, Western and Canadian Districts.

A World-Wide Christian Church

The Moravian Church in Herrnhut had a passion and a zeal for souls. They had the conviction that the God who had saved them, was calling them to share the good news to the whole world, especially those who had never heard of Jesus Christ. It was a passion and zeal that was so strong, that their small numbers did not deter them.

The Moravian Church has continued to spread, albeit slowly in comparison to other denominations. A reason for its relatively small size is that in evangelizing, the Moravians were not focusing on making more Moravians, but rather simply of winning people to Jesus Christ — who were then encouraged to become a member of whatever denomination they wished!

Today there are more than one million members of the Moravian Church in the world. Most of them live in eastern Africa. Other major Moravian centers are the Caribbean basin (U.S. Virgin Islands, Antigua, Jamaica, Tobago, Surinam, Guyana, St. Kitts, and the Miskito Coast of Honduras and Nicaragua), and South Africa. Though the Moravians played an important role in colonial American history, the church in North America numbers only about 60,000 (including Canada, Alaska, Labrador).

One of the reasons for the difference in membership between the United States and the rest of the world is that the Unitas Fratrum has asserted throughout its history that Christian fellowship recognizes no barrier of nation or race, and views its calling as bringing the good news of God’s infinite love to everyone, including some of the more remote places of the world.

The Moravian Unity

1957 marked the 500th anniversary of the founding of the Unitas Fratrum. At the General Synod that year, the Moravian Church was reorganized into more than a dozen semi-autonomous Provinces that remain part of a single global church known officially as the Unitas Fratrum.

Thus today the Unitas Fratrum, which has asserted throughout its history that Christian fellowship recognizes no barrier of nation or race, is still an international Unity with congregations in many parts of the world.

As of October 2024, there are now 25 Provinces of the Unity as well as 6 Mission Provinces (countries and regions that do not have the full status of a Unity province yet) and 15 Mission Areas in which the Moravian Church has only been working for a few years.

There are also two Unity Undertakings which are supported by the entire Unity of the Brethren (Star Mountain Rehabilitation Center in Ramallah, Palestine and the Unity Archive in Herrnhut).

Today, we celebrate our heritage and ministry with over 1.25 million Moravians. From Alaska to Tanzania, Ireland to Nicaragua, from Peru to Nepal, from Germany to Labrador, from South Africa to Ontario — Moravians can be found all over the world!

A Unity Synod is held every seven years to decide matters that affect the whole Moravian Church. The highest administrative body in each Province is the Synod, which meets every four years to direct missionary, educational, and publishing work. A Provincial Elders Conference is also elected, which functions between Synod meetings. Bishops, elected by Provincial Synods, are spiritual, not administrative, leaders of the church.

The Unitas Fratrum cherishes its unity as a valuable treasure entrusted to it by the Lord. It stands for the oneness of all humankind given by the reconciliation through Jesus Christ. Therefore the ecumenical movement is of its very lifeblood. For five centuries it has pointed towards the unity of the scattered children of God that they may become one in their Lord.

An Ecumenical Church

For more than five centuries the Moravian Church has proclaimed the gospel in all parts of the world. Its influence has far exceeded its numbers as it has cooperated with religious faiths on every continent and has been a visible part of the Body of Christ.

To this end, the Moravian Church in America, Northern Province is in full communion with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Episcopal Church (USA), the Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Methodist Church (USA), the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada and with the Anglican Church of Canada.

To be in full communion with our Christian brothers and sisters means that:

- We mutually recognize and value the diverse gifts present in each church;

- We respect each other as part of the body of Christ in the world today;

- We commit each church to cooperate in common ministries of evangelism, witness, and service;

- We recognize the validity of each other’s sacramental life and ministerial orders, allowing for the transfer of membership and the orderly exchange of clergy (subject to the regulations of church order and practice of each church);

- We commit each church to continuing to work for the visible unity of the Christian church – recognizing that this relationship of full communion is but a step toward the unity to which we are called.

The Moravian Church is a charter member of the World Council of Churches.

The Moravian Church in North America is a member of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site

On July 26, 2024 in New Delhi, India, it was announced that Moravian Church Settlements in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania/US; Gracehill, Northern Ireland/UK; and Herrnhut, Germany have been inscribed as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage Site.

The Historic Moravian Bethlehem District was founded in 1741, the historic settlements of Herrnhut were founded in 1722, and Gracehill was established in 1759. The three areas join as an extension of the Moravian settlement of Christiansfeld in Denmark, founded in 1773, which was added to the prestigious World Heritage List in 2015, to form a single World Heritage listing for Moravian Church Settlements.

The World Heritage designation recognizes that the historic Moravian Church Settlements represent the outstanding universal value of these historic settlements and the worldwide influence of the Moravian Church.

For more about the history of the Schoeneck congregation, please click here.

Some information on this page has been taken from the Moravian Church In America website. Copyright © 2010-2025, Interprovincial Board of Communications, Moravian Church in America. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from the Moravian Church Southern Province website. Copyright © 2018-2025, The Moravian Church in America. All Rights Reserved.

Some information on this page has been taken from the Unitas Fratrum website. Copyright © 2025, Unitas Fratrum. All Rights Reserved.

Photo Credit: John Amos Comenius, oil on canvas by Jürgen Ovens, 1650–70. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.